|

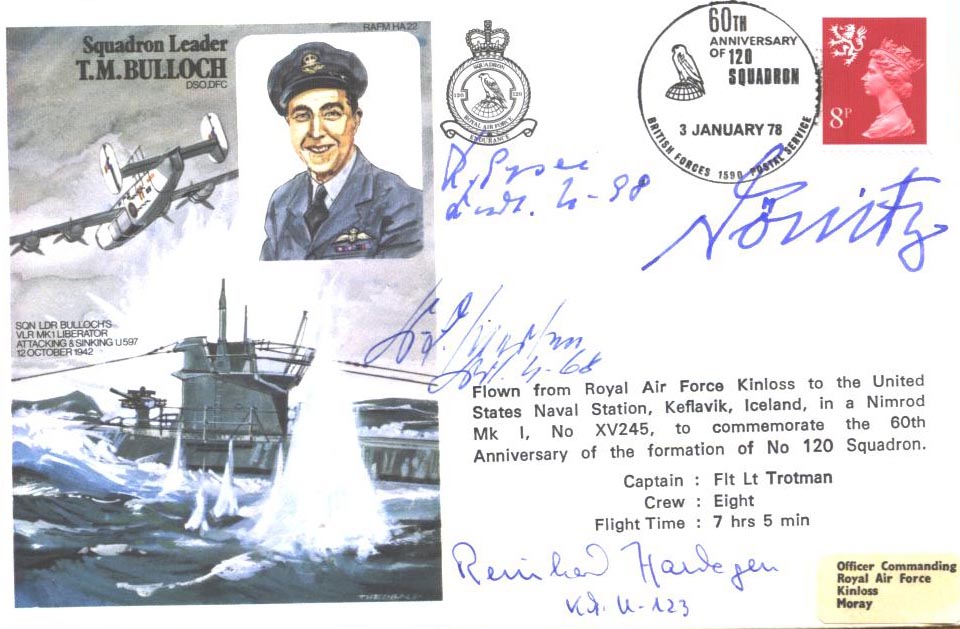

DONITZ Karl/ HARDEGEN Reinhard/GYSAE Robert

Großadmiral

Dönitz, Karl

* 16.09.1891 Berlin-Grünau

+ 24.12.1980 Aumühle

Awarded Knights Cross: 21.10.1940

as: Konteradmiral Befehlshaber der U-Boote

Awarded Oakleaves as the 223rd Recipient : 06.04.1943 as Großadmiral

Oberbefehlshaber Der Kriegsmarine und Befehlshaber der U-Boote

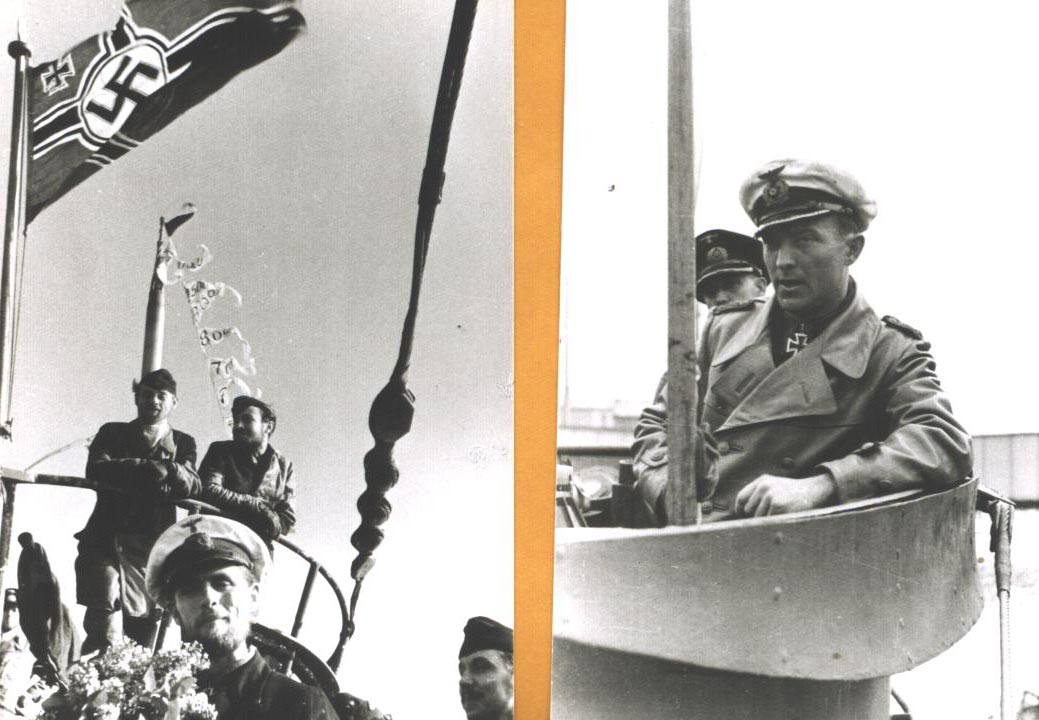

Karl Dönitz ; 16 September 1891 – 24 December 1980) was a German admiral who played a major role in the naval history of World War II. Dönitz succeeded Adolf Hitler as the head of state of Germany.

He began his career in the Imperial German Navy before World War I. In 1918, while he was in command of UB-68, the submarine was sunk by British forces and Dönitz was taken prisoner. While in a prisoner of war camp, he formulated what he later called Rudeltaktik ("pack tactic", commonly called "wolfpack"). At the start of World War II, he was the senior submarine officer in the Kriegsmarine. In January 1943, Dönitz achieved the rank of Großadmiral (grand admiral) and replaced Grand Admiral Erich Raeder as Commander-in-Chief of the Navy.

On 30 April 1945, after the death of Adolf Hitler and in accordance with Hitler's last will and testament, Dönitz was named Hitler's successor as head of state, with the title of President of Germany and Supreme Commander of the Armed Forces. On 7 May 1945, he ordered Alfred Jodl, Chief of Operations Staff of the OKW, to sign the German instruments of surrender in Rheims, France. Dönitz remained as head of the Flensburg Government, as it became known, until it was dissolved by the Allied powers on 23 May. At the Nuremberg trials, he was convicted of war crimes and sentenced to ten years' imprisonment; after his release, he lived quietly in a village near Hamburg until his death in 1980.

Battle of the Atlantic

In September 1939, Germany invaded Poland. Britain and France declared war on Germany, and World War II began. The Kriegsmarine was caught unprepared for war, having expected that war would break out in 1945, instead of 1939. The Z Plan was tailored for this assumption, calling for a balanced fleet with a greatly increased number of surface capital ships, including several aircraft carriers. At the time the war began, Dönitz's force included only 57 U-boats, many of them short-range, and only 22 oceangoing Type VIIs. He made do with what he had, while being harassed by Raeder and with Hitler calling on him to dedicate boats to military actions against the British fleet directly. These operations had mixed success; the aircraft carrier HMS Courageous and battleship Royal Oak were sunk, battleships HMS Nelson damaged and Barham sunk at a cost of some U-boats, diminishing the small quantity available even further. Together with surface raiders, merchant shipping lines were also attacked by U-boats.

Großadmiral Karl Dönitz

Commander of the submarine fleet

On 1 October 1939, Dönitz became a Konteradmiral (rear admiral) and "Commander of the Submarines" (Befehlshaber der Unterseeboote, BdU); on 1 September the following year, he was made a Vizeadmiral (vice admiral).

With the fall of France, Germany acquired U-boat bases at Lorient, Brest, St Nazaire, and La Pallice/La Rochelle. A communication centre was established at the Chateau de Pignerolles at Saint-Barthélemy-d'Anjou.[citation needed]

By 1941, the delivery of new Type VIIs had improved to the point where operations were having a real effect on the British wartime economy. Although production of merchant ships shot up in response, improved torpedoes, better U-boats, and much better operational planning led to increasing numbers of "kills". On 11 December 1941, following Hitler's declaration of war on the United States, Dönitz immediately planned for implementation of Operation Drumbeat (Unternehmen Paukenschlag) This targeted shipping along the East Coast of the United States. Carried out the next month with only nine U-boats (all the larger Type IX), it had dramatic and far-reaching results. The U.S. Navy was entirely unprepared for antisubmarine warfare despite having had two years of British experience to draw from, and committed every imaginable mistake. Shipping losses, which had appeared to be coming under control as the Royal Navy and Royal Canadian Navy gradually adapted to the new challenge, skyrocketed.

On at least two occasions, Allied success against U-boat operations led Dönitz to investigate. Among reasons considered were espionage and Allied interception and decoding of German naval communications (the naval version of the Enigma cipher machine). Both investigations into communications security came to the conclusion espionage was more likely, or else the Allied successes had been accidental. Nevertheless, Dönitz ordered his U-boat fleet to use an improved version of the Enigma machine (one with four rotors, which was more secure than the three-rotor version it replaced), the M4, for communications within the fleet, on 1 February 1942. The Kriegsmarine was the only branch to use this improved version; the rest of the Wehrmacht (German armed forces) continued to use their then-current three-rotor versions of the Enigma machine. The new system was termed "Triton" ("Shark" to the Allies). For a time, this change in encryption between submarines caused considerable difficulty for Allied codebreakers; it took 10 months before Shark traffic could be read (see also Ultra codebreaking and Cryptanalysis of the Enigma).

By the end of 1942, the production of Type VII U-boats had increased to the point where Dönitz was finally able to conduct mass attacks by groups of submarines, a tactic he called Rudel (group or pack) and became known as "wolfpack" in English. Allied shipping losses shot up tremendously, and serious concern existed for a while about the state of British fuel supplies.

During 1943, the war in the Atlantic turned against the Germans, but Dönitz continued to push for increased U-boat construction and entertained the notion that further technological developments would tip the war once more in Germany's favour, briefing the Führer to that effect. At the end of the war, the German submarine fleet was by far the most advanced in the world, and late-war examples such as the Type XXI U-boat served as models for Soviet and American construction after the war. The Schnorchel (snorkel) and Type XXI boats appeared late in the war because of Dönitz's personal indifference, at times even hostility, to new technology he perceived as disruptive to the production process.[11] His opposition to the larger Type IX was not unique; Admiral Thomas C. Hart, commander of the United States Asiatic Fleet in the Philippines at the outbreak of the Pacific War, opposed fleet boats like the Gato and Balao classes as "too luxurious".[12]

Dönitz was deeply involved in the daily operations of his boats, often contacting them up to 70 times a day with questions such as their position, fuel supply. and other "minutiae". This incessant questioning hastened the compromise of his ciphers by giving the Allies more messages to work with. Furthermore, replies from the boats enabled the Allies to use direction finding (HF/DF, called "Huff-Duff") to locate a U-boat using its radio, track it and attack it (often with aircraft able to sink it with impunity).

Dönitz wore on his uniform the special grade of the U-Boat War Badge with diamonds, his U-Boat War badge from World War I and his World War I Iron Cross 1st Class with World War II clasp.

Commander-in-chief and Grand Admiral

On 30 January 1943, Dönitz replaced Erich Raeder as Commander-in-Chief of the Navy (Oberbefehlshaber der Kriegsmarine) and Großadmiral (grand admiral) of the Naval High Command (Oberkommando der Marine). His deputy, Eberhard Godt, took over the operational command of the U-boat force[13] Dönitz was able to convince Hitler not to scrap the remaining ships of the surface fleet. Despite hoping to continue to use them as a fleet in being, the Kriegsmarine continued to lose what few capital ships it had. In September, the battleship Tirpitz was put out of action for months by a British midget submarine, and was sunk a year later by RAF bombers at anchor in Norway. In December, he ordered the battleship Scharnhorst (under Konteradmiral Erich Bey) to attack Soviet-bound convoys, after reconsidering her success in the early years of the war with sister ship Gneisenau, but she was sunk in the resulting encounter with superior British forces led by the battleship HMS Duke of York.

President of Germany

Hitler's last will and testament shows that Dönitz was chosen to succeed Hitler as Germany's president.

In the final days of the war, after Hitler had taken refuge in the Führerbunker beneath the Reich Chancellery garden in Berlin, Reichsmarschall Hermann Göring was considered the obvious successor to Hitler, followed by Reichsführer-SS Heinrich Himmler. Göring, however, infuriated Hitler by radioing him in Berlin asking for permission to assume leadership of the Reich. Himmler also tried to seize power by entering into negotiations with Count Bernadotte. On 28 April 1945, the BBC reported Himmler had offered surrender to the western Allies and that the offer had been declined. From mid-April 1945, elements of the last Reich government and the Commander of the Navy, Admiral Karl Dönitz, moved into the buildings of the Stadtheide Barracks in Plön. In his last will and testament, dated 29 April 1945, Hitler named Dönitz his successor as Staatsoberhaupt (Head of State), with the titles of Reichspräsident (President) and Supreme Commander of the Armed Forces. The same document named Propaganda Minister Joseph Goebbels as Head of Government with the title of Reichskanzler (Chancellor). Furthermore, Hitler expelled both Göring and Himmler from the party.[15]

Rather than designate one person to succeed him as Führer, Hitler reverted to the old arrangement in the Weimar Constitution. He believed the leaders of the air force (Luftwaffe) and SS (Schutzstaffel) had betrayed him. Since the Kriegsmarine had been too small to affect the war in a major way, its commander, Dönitz, became the only possible successor as far as Hitler was concerned more or less by default.[16][page needed]

On 1 May, the day after Hitler's own suicide, Goebbels committed suicide.[17] Dönitz thus became the sole representative of the crumbling German Reich. He appointed Finance Minister Count Ludwig Schwerin von Krosigk as "Leading Minister" (Krosigk had declined to accept the title of Chancellor), and they attempted to form a government.

On 1 May, Dönitz announced that Hitler had fallen and had appointed him as his successor. On 2 May, the new government of the Reich fled to Flensburg-Mürwik before the approaching British troops. That night, Dönitz made a nationwide radio address in which he announced Hitler's death and said the war would continue in the east "to save Germany from destruction by the advancing Bolshevik enemy". However, Dönitz knew Germany's position was untenable and the Wehrmacht was no longer capable of offering meaningful resistance. During his brief period in office, he devoted most of his effort to ensuring the loyalty of the German armed forces and trying to ensure German troops would surrender to the British or Americans and not the Soviets. He feared vengeful Soviet reprisals, and hoped to strike a deal with the western Allies.[16] In the end, Dönitz's tactics were moderately successful, enabling about 1.8 million German soldiers to escape Soviet capture.[18]

Flensburg government

The rapidly advancing Allied forces limited the Dönitz government's jurisdiction to an area around Flensburg near the Danish border. Dönitz's headquarters were located in the Naval Academy in Mürwik, a suburb of Flensburg. Accordingly, his administration was referred to as the Flensburg government. The following is Dönitz's description of his new government:

These considerations (the bare survival of the German people), which all pointed to the need for the creation of some sort of central government, took shape and form when I was joined by Graf Schwerin-Krosigk. In addition to discharging his duties as Foreign Minister and Minister of Finance, he formed the temporary government we needed and presided over the activities of its cabinet. Though restricted in his choice to men in northern Germany, he nonetheless succeeded in forming a workmanlike cabinet of experts. The picture of the military situation as a whole showed clearly that the war was lost. As there was also no possibility of effecting any improvement in Germany's overall position by political means, the only conclusion to which I, as head of state, could come was that the war must be brought to an end as quickly as possible in order to prevent further bloodshed.

— Karl Dönitz, Ten Years and Twenty Days

Late on 1 May, Himmler attempted to make a place for himself in the Flensburg government. The following is Dönitz's description of his showdown with Himmler:

At about midnight he arrived, accompanied by six armed SS officers, and was received by my aide-de-camp, Walter Luedde-Neurath. I offered Himmler a chair and sat down at my desk, on which lay, hidden by some papers, a pistol with the safety catch off. I had never done anything of this sort in my life before, but I did not know what the outcome of this meeting might be.

I handed Himmler the telegram containing my appointment. "Please read this," I said. I watched him closely. As he read, an expression of astonishment, indeed of consternation, spread over his face. All hope seemed to collapse within him. He went very pale. Finally he stood up and bowed. "Allow me," he said, "to become the second man in your state." I replied that was out of the question and that there was no way I could make any use of his services.

Thus advised, he left me at about one o'clock in the morning. The showdown had taken place without force, and I felt relieved.

— Karl Dönitz, as quoted in The Decline and Fall of Nazi Germany and Imperial Japan

On 4 May, German forces in the Netherlands, Denmark, and northwestern Germany under Dönitz's command surrendered to Field Marshal Sir Bernard Law Montgomery at Lüneburg Heath just southeast of Hamburg, signalling the end of World War II in northwestern Europe.

A day later, Dönitz sent Admiral Hans-Georg von Friedeburg, his successor as the commander in chief of the Kriegsmarine, to U.S. General Dwight D. Eisenhower's headquarters in Rheims, France, to negotiate a surrender to the Allies. The Chief of Staff of OKW, Generaloberst (Colonel-General) Alfred Jodl, arrived a day later. Dönitz had instructed them to draw out the negotiations for as long as possible so that German troops and refugees could surrender to the Western powers, but when Eisenhower let it be known he would not tolerate their stalling, Dönitz authorised Jodl to sign the instrument of unconditional surrender at 1:30 on the morning of 7 May. Just over an hour later, Jodl signed the documents. The surrender documents included the phrase, "All forces under German control to cease active operations at 23:01 hours Central European Time on 8 May 1945." At Stalin's insistence, on 8 May, shortly before midnight, (Generalfeldmarschall) Wilhelm Keitel repeated the signing in Berlin at Marshal Georgiy Zhukov's headquarters, with General Carl Spaatz of the USAAF present as Eisenhower's representative. At the time specified, World War II in Europe ended.

On 23 May, the Dönitz government was dissolved when Großadmiral Dönitz was arrested by an RAF Regiment task force under the command of Squadron Leader Mark Hobden. The Großadmiral's Kriegsmarine flag, which was removed from his headquarters can be seen at the RAF Regiment Heritage Centre at RAF Honington. Generaloberst Jodl, Reichsminister Speer and other members were also handed over to troops of the King's Shropshire Light Infantry at Flensburg. His ceremonial baton, awarded to him by Hitler, can be seen in the regimental museum of the KSLI in Shrewsbury Castle.

Korvettenkapitän

Hardegen, Reinhard

* 18.03.1913 Bremen

Knights Cross: 23.01.1942

as: Kapitänleutnant Kommandant U-123

Awarded Oakleaves as the 89th Recipient : 23.04.1942 as Kapitänleutnant

Kommandant U-123

Reinhard Hardegen

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Korvettenkapitän Reinhard Hardegen (born 18 March 1913) is a German U-boat commander who sank 22 ships, amounting to 115,656 gross register tons (GRT) sunk, making him the 24th most successful commander in World War II. He was never known to be an ardent Nazi supporter, however. After the war, he spent a year in British captivity before running a successful oil company and serving in Bremen's Parliament for over 32 years

Early life

Born in Bremen, Germany, Hardegen dreamed of a career in the German navy from an early age. Following his graduation from high school he enrolled in the Reichsmarine as a Seekadett, sailing around the world in the light cruiser Karlsruhe in 1933. In 1935, Hardegen was transferred as a Marineflieger in the Kriegsmarine's air arm. He trained as a naval aircraft observer and, after, as a pilot, and was promoted to leutnant on 1 October 1936. In early 1939, he crashed his aircraft and was hospitalized for six months. Later that year, Hermann Göring declared all aircraft in German service as belonging to the Luftwaffe, effectively canceling the Navy Air Arm. Hardegen was then transferred to the Ubootwaffe and began training as a U-boat commander.

World War II

Hardegen served as 1.WO (First Watch Officer) under Kapitänleutnant Georg-Wilhelm Schulz aboard U-124 and, after two war patrols, was given his own command, the Type IID U-boat U-147, operating out of Kiel, on 11 December 1940. The boat was ready for its first patrol shortly before the new year and, after visiting the U-boat base in Bergen, U-147 was ordered to patrol the convoy routes north of the Hebrides.

On the second day of the patrol, Hardegen fired a torpedo which failed to detonate against a large merchant ship, before being forced to submerge after mistaking a destroyer for a merchant ship. During the dive, the tower hatch was damaged, forcing U-147 to resurface after a short while to make feverish repairs only a few hundred meters from the destroyer. The gathering darkness, however, saved the boat from being detected. The water leaks had damaged the diesel engines aboard the boat, forcing Hardegen to use his electric motors when, later in the night, he saw another merchant passing by. Although slowed, the U-boat had enough speed to close the distance and launch a torpedo which sank the freighter. After interrogating the crew, Hardegen learned it was the Norwegian steamer Augvald 4,811 GRT. A few days later, Hardegen again attacked two freighters, only to find his torpedoes missing or failing to detonate. Shortly thereafter, he was ordered back to Kiel.

After completing the patrol, Hardegen was given command of U-123, a Type IXB U-boat operating out of Lorient. Hardegen's first patrol with U-123 started on 16 June 1941, with a course for West African waters to attack British shipping around Freetown.

On 20 June, Hardegen sank the neutral Portuguese vessel Ganda, mistaking her for a British freighter. Dönitz later ordered all references to this sinking deleted from the journals of U-123 and the matter received little attention.[4] This was the only of two known alterations of the Kriegstagebuch ordered by Dönitz, the other being in regard to the sinking of the liner SS Athenia. After receiving depth charge damage, U-123 returned to Lorient, docking on 23 August, with a total score of five ships for 21,507 GRT.

His next patrol, in October 1941, took him to the North Atlantic. On 20 October he intercepted a convoy and attacked the British auxiliary cruiser HMS Aurania (13,984 tons). Although badly damaged, the cruiser was towed to harbour for repairs. Some of the crew abandoned the cruiser, however, and Hardegen picked up a survivor who was brought back to France as a prisoner of war. This led Hardegen to claim the sinking. A day later, Hardegen shadowed another convoy until aircraft forced him to submerge and he lost contact. After weeks of patrolling the area south of Greenland, U-123 returned to Lorient.

First Drumbeat patrol

Hardegen's aircrash in 1936 had left him with internal injuries, a bleeding stomach and a shortened leg. He had been classified as unfit for U-boat duty, but the paperwork had not caught up with him until now. Dönitz learned of this, but needed experienced commanders for Operation Drumbeat, the offensive into American waters, and so Hardegen was allowed to go on two more patrols.

On 23 December 1941, U-123 left for the first phase of Drumbeat. Five boats, which was all Dönitz could muster, were sent towards the American coast, to take advantage of the confusion in the Eastern Seaboard defense networks shortly after the declaration of war. Hardegen was ordered to penetrate the inshore areas around New York City, however due to the need for strict operational secrecy for this task, no mapping of the area was issued from stores in Lorient, and Hardegen had only large nautical charts as well as a Knaur pocket atlas (of his own), for navigation.[6] Following his foray into New York, Hardegen was to target merchant shipping off Cape Hatteras.

On 12 January 1942, Hardegen drew first blood, sinking the British freighter Cyclops (9,076 GRT). On 14 January, he reached the approaches to New York harbour. Hardegen decided to proceed into the harbour on the surface.[7] The still brightly burning shore lights helped immensely with the navigation through the unknown waters. During the morning hours, U-123 sighted the Norwegian tanker Norness (9,577 GRT) off the coast of Long Island and sank her, although it took five torpedoes due to malfunctions.

Following this, Hardegen decided to bottom (place the boat on the ocean bottom) the boat and wait for nightfall before proceeding into the harbour itself. During the night of 15 January, Hardegen entered the harbour, nearly beaching the boat when he mistook shorelight for a light ship.[8] The crew of U-123 were elated when they came within the sight of the city itself, all lights burning brightly, but Hardegen did not linger long, due to the lack of merchant traffic. He did sink the British tanker Coimbra (6,768 GRT) on his way out.

Hardegen then proceeded south along the coast, submerging during the day and surfacing at night. Apart from one air attack on 16 January, Hardegen did not experience any resistance from the United States Navy or Air Force. During the night of 19 January, Hardegen sank three freighters off Cape Hatteras in shallow waters close to shore. A couple of hours later, he happened upon five more merchants traveling in a group and attacked them with his last two torpedoes and his 105 mm deck gun, sinking a freighter and claiming the tanker Malay (8,207 GRT) as well.[10] Although badly damaged, Malay, traveling empty, had enough buoyancy to stay afloat and managed to make its way to New York under her own power five days later.

With all torpedoes expended, and the port diesel engine not functioning optimally, Hardegen decided to set course for home. Just before dawn, the Norwegian whaling factory Kosmos II (16,699 GRT) was spotted only 400 metres (1,300 ft) away. The skipper of Kosmos, Einar Gleditsch, decided to ram U-123, ordering full speed ahead. Hardegen, realizing that the whaler was too close for him to submerge, turned hard to port and ordered full ahead. With its port engine unable to deliver top RPMs, U-123 only just managed to keep ahead of the tanker, and it took over an hour for Hardegen to gain enough of a lead to have room to maneuver. This encounter was, ironically, the most dangerous for U-123 on its first trip, telling volumes about the lack of US Navy preparedness.

During the return journey, he spotted and sank the British freighter Culebra (3,400 GRT) on 25 January using the deck gun, but return fire from the freighter damaged the boat. The following night, the Norwegian tanker Pan Norway (9,231 GRT) was attacked and sunk. After the attack, Hardegen ordered a nearby neutral freighter to pick up the survivors, although he had to repeat his order after the Greek captain decided to steam off without picking up all of the crew. This sinking brought the tally for the first patrol to nine ships sunk for a total of 53,173 GRT over a two-week period, although Hardegen also claimed Malay for a total of 66,135 GRT.[16] The success of Hardegen's Drumbeat prompted Dönitz to radio a congratulatory signal on 20 January, "An den Paukenschläger Hardegen. Bravo! Gut gepaukt. Dönitz." (For the drum-beater Hardegen. Well done! Good beating. Dönitz.)

On 23 January, Hardegen received another signal, confirming he had been awarded the Knight's Cross of the Iron Cross (Ritterkreuz des Eisernen Kreuzes) for sinking over 100,000 GRT of enemy shipping. He returned home to Lorient on 9 February and received a hero's welcome.Second Drumbeat patrol

On 2 March 1942, Hardegen left for his final patrol, his second to American waters. The first successes were achieved when Hardegen sank the American tanker Muskogee (7,034 GRT) on 22 March and the British tanker Empire Steel (8,150 GRT) on 24 March. The latter attack expended four torpedoes, however, as one malfunctioned and one was fired without having been aimed. The tanker, carrying gasoline, burned fiercely for five hours before sinking and no survivors could be spotted. The somber crew of U-123 nicknamed the night the "Tanker Torch night".[19]

On 26 March, Hardegen attacked the American Q-ship USS Atik (3,000 GRT), mistaking it for a merchant freighter. After torpedoing the ship, Hardegen surfaced to sink her with the deck guns, only to find the Atik trying to ram him and opening fire on him with guns that had been concealed behind false bulwarks. Making a getaway on the surface, U-123 received eight hits and one of the crew members was fatally wounded. Approaching the Atik submerged, Hardegen sank her with another torpedo.

Hardegen's second patrol was along the Florida coast. He reached the target area in late March, attacking the American tanker Liebre (7,057 GRT) on 1 April with his deck gun. Although the tanker was badly damaged, an approaching patrol craft forced Hardegen to submerge and leave the area. Liebre was towed to port and was ready to sail again by mid-July.[ On the night of 8 April, U-123 was positioned off the shore of St. Simons Island, Georgia and torpedoed and sank two tankers: the SS Oklahoma (9,264 GRT) and the Esso Baton Rouge (7,989 GRT). The two tankers were sunk in such shallow water, however, that they were re-floated and put back into service. During the night of 9 April, U-123 sank the cold storage motor ship SS Esparta (3,365 GRT).

On the night of 11 April, U-123 torpedoed and sank the SS Gulfamerica (8,801 GRT) about two miles off the coast of Jacksonville, Florida. The Gulfamerica was on its maiden voyage from Philadelphia to Port Arthur, Texas with 90,000 barrels of fuel oil. After hitting her with a torpedo, Hardegen closed in for the kill with his deck gun. Noting the already large crowds gathering on the beach to watch the spectacle, as well as all the beach houses just beyond the Gulfamerica, Hardegen decided to manoeuver around the tanker and attack from the land side. The move was quite hazardous, as the U-boat was clearly illuminated to any onshore weapons, and the shallow waters forced it to take up station only 250 metres (820 ft) from the tanker, which risked return fire from the tanker as well as getting caught in a blaze if the oil spilling out caught fire. The highways leading from Jacksonville were soon thronged with curious people trying to get to the beach to look at the spectacle. After firing for some time with the deck gun, the tanker was ablaze and Hardegen decided to leave. Already planes were overhead trying to locate the submarine by parachute lights, while a destroyer and several smaller patrol boats were closing in.

Forced by an aircraft to crash dive, U-123 found itself on the bottom, only 20 metres (66 ft) under the surface, when the destroyer, USS Dahlgren dropped six depth charges. Taking heavy damage and believing the destroyer would move in for another attack, Hardegen ordered the secret codes and machinery destroyed and the boat abandoned. As the commander, he was to open the tower hatch to allow the crew to escape using the escape gear; however, he was gripped by a paralyzing fear and was unable to proceed with the evacuation. Luckily for him, the Dahlgren, for reasons unknown, failed to drop any more depth charges and, after a short time, moved away, allowing the U-123 to complete emergency repairs and limp towards deeper waters. Hardegen would later tell Michael Gannon, "Only because I was too scared was I not captured."

On the night of 13 April, U-123 attacked the US freighter SS Leslie (2,609 GRT) with its last torpedo and Hardegen's fiftieth torpedo launch. It sank quickly just off Cape Canaveral.[28] About two hours after this attack, Hardegen shelled the Swedish motor ship Korsholm (5,353 GRT) under British charter, and sank her within twenty minutes. He did, however, mistake the freighter for a tanker.

At this point in his second patrol, Hardegen claimed ten ships for a total of 74,815 GRT, whereas in reality he had sunk nine, if counting the two tankers later refloated, for a total of a still respectable 52,336 GRT. To sum up his patrol, Hardegen chose the lyrical approach, sending the following signal to BdU:

Sieben Tankern schlug die letze Stund,

die U-Falle sank träger.

Zwei Frachter liegen mit auf Grund,

Versenkt vom Paukenschläger.

(For seven tankers the last hour has passed

the U-boat Trap sank slower.

Two freighters lie on the bottom too,

sunk by the drum-beater.)

Setting course for home, Hardegen sighted the freighter SS Alcoa Guide (4,834 GRT) on 16 April and sank her with fire from the 105mm deck gun, as well as the 37mm and 20mm flak guns.[30] On 23 April, Hardegen received a signal confirming his award of the Oak Leaves to his Knights Cross. On 2 May, U-123 docked at Lorient, ending Hardegen's career as an active U-boat commander, although he commanded the boat for a final journey, bringing her back to Kiel for some necessary repairs in May 1942.

Before this, however, he and fellow Oak Leaves winner Erich Topp were invited to a dinner with Adolf Hitler. During the dinner, Hardegen caused great embarrassment by sharply criticizing the lack of priorities given to the U-boat war by Der Führer, causing Hitler to go red with anger and Hardegen to receive a reprimand from Chief of Staff Alfred Jodl, to which Hardegen replied, "The Führer has a right to hear the truth, and I have a duty to speak it."

Shore duty

On 31 July 1942, Hardegen relinquished command of U-123 and took up duties as an instructor in the 27th U-boat Training Flotilla in Gotenhafen. In March 1943, Kapitänleutnant Hardegen became chief of U-boat training of the torpedo school at Marineschule Mürwik, before taking up a position in the Torpedowaffenamt (torpedo weapon department), where he oversaw testing and development of new acoustic and wired torpedoes. In his last posting, he served as battalion commander in Marine Infanterie Regiment 6 from February 1945 until the end of the war. The unit took part in fierce fighting against the British in the area around Bremen, and most of the officers were killed. Hardegen stated that his survival was due to his being hospitalized with a severe case of diphtheria. For the last few days of the war, Hardegen served on Dönitz's staff in Flensburg, where he was arrested by British troops.

Later life

After the war, Hardegen was mistaken for a SS officer with the same last name, and it took him a year and a half to assemble the evidence to convince the Allied interrogators of his real identity. He returned home in November 1946, where he started as a businessman, first on a bike and then in a car. In 1952, he started an oil trading company, which he built up into a great success. Hardegen also served as a member of Parliament (Bürgerschaft of Bremen) for the Christian Democrats in his hometown of Bremen for 32 years. He turned 100 in March 2013 in very good health, winning golf trophies and still driving a car.

Kapitän zur See

Merten, Karl-Friedrich

* 15.08.1905 Posen

+ 02.05.1993 Waldshut-Tiengen/Württemberg

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Karl-Friedrich Merten (15 August 1905 – 2 May 1993) commanded the U-boat U-68 in Nazi Germany's Kriegsmarine during World War II. He received the Knight's Cross of the Iron Cross with Oak Leaves, a decoration awarded to recognise extreme battlefield bravery or outstanding military leadership. Kapitän zur See (captain at sea) Merten is credited with the sinking of 27 ships for a total of 170,151 gross register tons (GRT) of allied shipping.

Born in Posen, Merten joined the Reichsmarine (navy of the Weimar Republic) in 1926. After a period of training on surface vessels and service on various torpedo boats he served on the light cruisers Karlsruhe and Leipzig during the non-intervention patrols of the Spanish Civil War. At the outbreak of World War II, he was stationed on the battleship Schleswig-Holstein, participating in the Battle of Westerplatte and Battle of Hel. He transferred to the U-boat service in 1940, at first serving as a watch officer on U-38 before taking command of U-68 in early 1941. Commanding U-68 on five war patrols, patrolling in the Atlantic Ocean, the Caribbean Sea and the Indian Ocean, he was awarded Knight's Cross of the Iron Cross on 13 June 1942 and the Oak Leaves to his Knight's Cross on 16 November 1942. On the second patrol, Merten helped rescue the crews of the auxiliary cruiser Atlantis and the refuelling ship Python, which had been sunk by the Royal Navy. In January 1943 Merten became the commander of the 26th U-boat Flotilla and in March 1943, Merten was given command of the 24th U-boat Flotilla. In February 1945, he was posted to the posted to the Führer Headquarters in Berlin. At the end of the war, he was taken prisoner of war by US forces and released again in late June 1945.

After the war, Merten worked in salvaging sunken ships in the Rhine river. In November 1948, Merten was arrested by the French and accused of allegedly wrongful sinking of the French tanker Frimaire in June 1942. He was acquitted and later worked in the shipbuilding industry. Merten, who had written his memoir and books on U-boat warfare, died of cancer on 2 May 1993 in Waldshut-Tiengen, Germany.

Korvettenkapitän

Gysae, Robert

* 04.01.1911 Berlin-Charlottenburg

+ 28.04.1989 Wilhelmshaven

Awarded Knights Cross: 31.12.1941

as: Kapitänleutnant Kommandant U-98

Awarded Oakleaves as the 250th Recipient : 31.05.1943 as Kapitänleutnant

Kommandant U-177

Robert Gysae (14 January 1911 – 26 April 1989) was a Korvettenkapitän with the Kriegsmarine during World War II. He was also a recipient of the Knight's Cross of the Iron Cross with Oak Leaves (German: Ritterkreuz des Eisernen Kreuzes mit Eichenlaub). The Knight's Cross of the Iron Cross and its higher grade Oak Leaves was awarded to recognise extreme battlefield bravery or successful military leadership. Gysae commanded U-98 and U-177, sinking twenty-five ships on eight patrols, for a total of 146,815 gross register tons (GRT) tons of Allied shipping, to become the fifteenth highest scoring U-Boat ace of World War II.

Career

Gysae joined the Reichsmarine in 1931 and served on torpedo boats before transferring to the U-bootwaffe ("U-boat force") in April 1940. In October 1940 he was appointed commander of the Type VIIC U-boat U-98, unusually without serving any time as either 1.WO (1. Wachoffizier, "1st Watch Officer") or Kommandantenschüler ("Commander-in-Training") on any other U-boats. After six patrols in the north Atlantic in command of U-98, in March 1942 he transferred to the Type IXD2 U-boat U-177 for another two patrols, this time operating off South Africa and Portuguese East Africa. He sank a total of 25 ships, including the armed merchant cruiser HMS Salopian.

On 28 November 1942 off the coast of Natal Province, Gysae sank the 6,796 ton British troop ship RMS Nova Scotia with three torpedoes. She was carrying 780 Italians; a mixture of prisoners of war and civilian internees. Gysae rescued two survivors to identify the ship, who turned out to be Italian merchant sailors. Mindful of the Laconia Order issued two months previously, Gysae radioed the BdU, who ordered him to continue his patrol. The BdU notified the Portuguese authorities, who sent the frigate NRP Afonso de Albuquerque from Lourenço Marques to help. Of 1,052 people from the Nova Scotia only 194 survived: 192 rescued by the frigate and two others in subsequent days. 858 were killed, including 650 Italians. January 1944 he became commander of 25th U-boat Flotilla, a training flotilla based at Gotenhafen. In April 1945, during the last month of the war, Gysae commanded the Marinepanzerjagd-Regiment 1, a naval anti-tank regiment. After the war he served in the Deutscher Minenräumdienst ("German Mine Sweeping Administration") for more than two years. In 1956 he joined the Bundesmarine, serving for four years as Navy attaché in the United States, and then three years as commander of Marinedivision Nordsee with the rank of Flottillenadmiral before retiring in 1970. He died in 1989 aged 78.

Ships attacked

During his career Gysae sunk 24 commercial ships for 136,266 GRT, one auxiliary warship of 10,549 GRT, and damaged one ship for 2,588 GRT.

Date

U-Boat

Name of Ship

Nationality

Tonnage

Fate

27 March 1941 U-98 Koranton United Kingdom 6,695 Sunk at 59°N 27°W

4 April 1941 U-98 Helle Norway 2,467 Sunk at 59°06′N 24°12′W

4 April 1941 U-98 Welcombe United Kingdom 5,122 Sunk at 59°09′N 23°40′W

9 April 1941 U-98 Prins Willem II Netherlands 1,304 Sunk at 59°50′N 24°25′W

13 May 1941 U-98 HMS Salopian Royal Navy 10,549 Sunk at 59°04′N 38°15′W

20 May 1941 U-98 Rothermere United Kingdom 5,356 Sunk at 57°48′N 41°36′W

21 May 1941 U-98 Marconi United Kingdom 7,402 Sunk at 58°N 41°W

9 July 1941 U-98 Designer United Kingdom 5,945 Sunk at 42°59′N 31°40′W

9 July 1941 U-98 Inverness United Kingdom 4,897 Sunk at 42°46′N 32°45′W

16 September 1941 U-98 Jedmoor United Kingdom 4,392 Sunk at 59°N 10°W

15 February 1942 U-98 Biela United Kingdom 5,298 Sunk at 42°55′N 45°40′W

2 November 1942 U-177 Aegeus Greece 4,538 Sunk at 32°30′S 16°00′E

9 November 1942 U-177 Cerion United Kingdom 2,588 Damaged at 35°58′S 26°37′E

19 November 1942 U-177 Scottish Chief United Kingdom 7,006 Sunk at 30°39′S 34°41′E

20 November 1942 U-177 Pierce Butler United States 7,191 Sunk at 29°40′S 36°35′E

28 November 1942 U-177 RMS Nova Scotia United Kingdom 6,796 Sunk at 28°30′S 33°00′E

30 November 1942 U-177 Llandaff Castle United Kingdom 10,799 Sunk at 27°20′S 33°40′E

7 December 1942 U-177 Saronikos Greece 3,548 Sunk at 24°46′S 35°30′E

12 December 1942 U-177 Empire Gull United Kingdom 6,408 Sunk at 26°15′S 34°40′E

14 December 1942 U-177 Sawahloento Netherlands 3,085 Sunk at 31°02′S 34°00′E

28 May 1943 U-177 Agwimonte United States 6,679 Sunk at 34°57′S 19°33′E

28 May 1943 U-177 Storaas Norway 7,886 Sunk at 34°57′S 19°33′E

6 July 1943 U-177 Jasper Park Canada 7,129 Sunk at 32°52′S 42°15′E

10 July 1943 U-177 Alice F. Palmer United States 7,176 Sunk at 26°30′S 44°20′E

29 July 1943 U-177 Cornish City United Kingdom 4,952 Sunk at 27°20′S 52°10′E

5 August 1943 U-177 Efthalia Mari Greece 4,195 Sunk at 24°21′S 48°55′E

Superb cover (#77 of #100 ) signed by all four with pictures

Price: $230.00

Please contact us before ordering to confirm availability and shipping costs.

Buy now with your credit card

other ways to buy

|